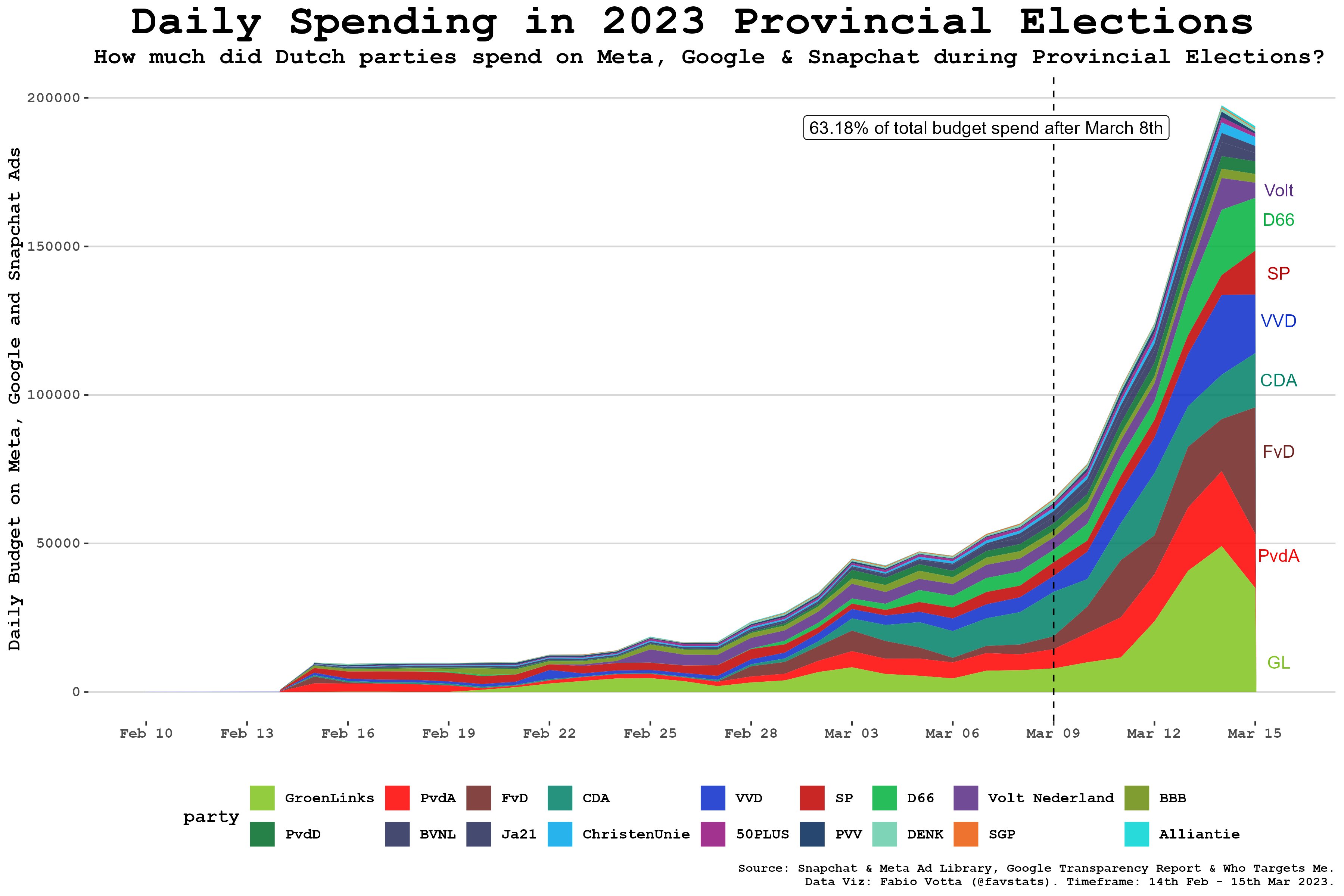

Digital advertising has become an integral part of political campaigning in recent years, and the 2023 Dutch provincial elections (15th March) were no exception. Political parties vied for the attention of potential voters across a range of digital platforms (including YouTube, Facebook, Instagram, and Snapchat), with spending totaling €1.31 million in the 30 days leading up to the election

Here, I take a deep dive into the world of digital advertising during the Dutch provincial elections, analyzing the spending patterns of political parties and examining the various targeting methods used to reach potential voters.

Digital Campaign Spending

Overall, Dutch political parties spent a total of €1.36M on digital ads in the 30 days leading up to the provincial elections. This figure includes spending on Google, Meta (Facebook and Instagram), and Snapchat. This represents roughly 20.8% of the total budget that was spent by these parties during the election campaign.

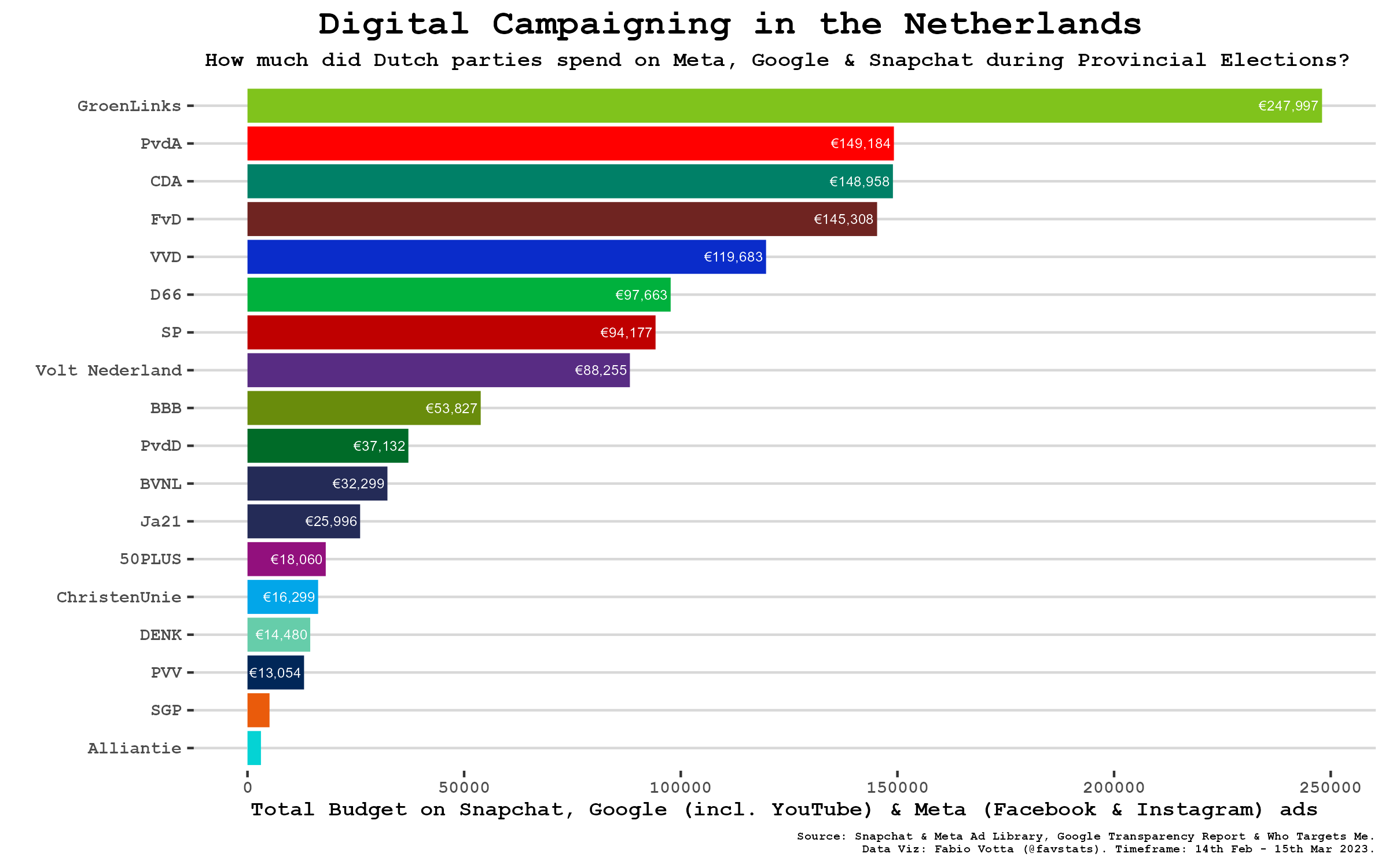

It’s worth noting that there was significant variation in the amount that each party spent on digital ads. GroenLinks was the biggest spender on digital ads, with a total spend of €248K. This was followed by the PvdA at €149K, and the CDA also at €149K. The FvD was a close fourth with a total spend of €145K in the last 30 days before the election.

Digital Spending compared to Total Budget

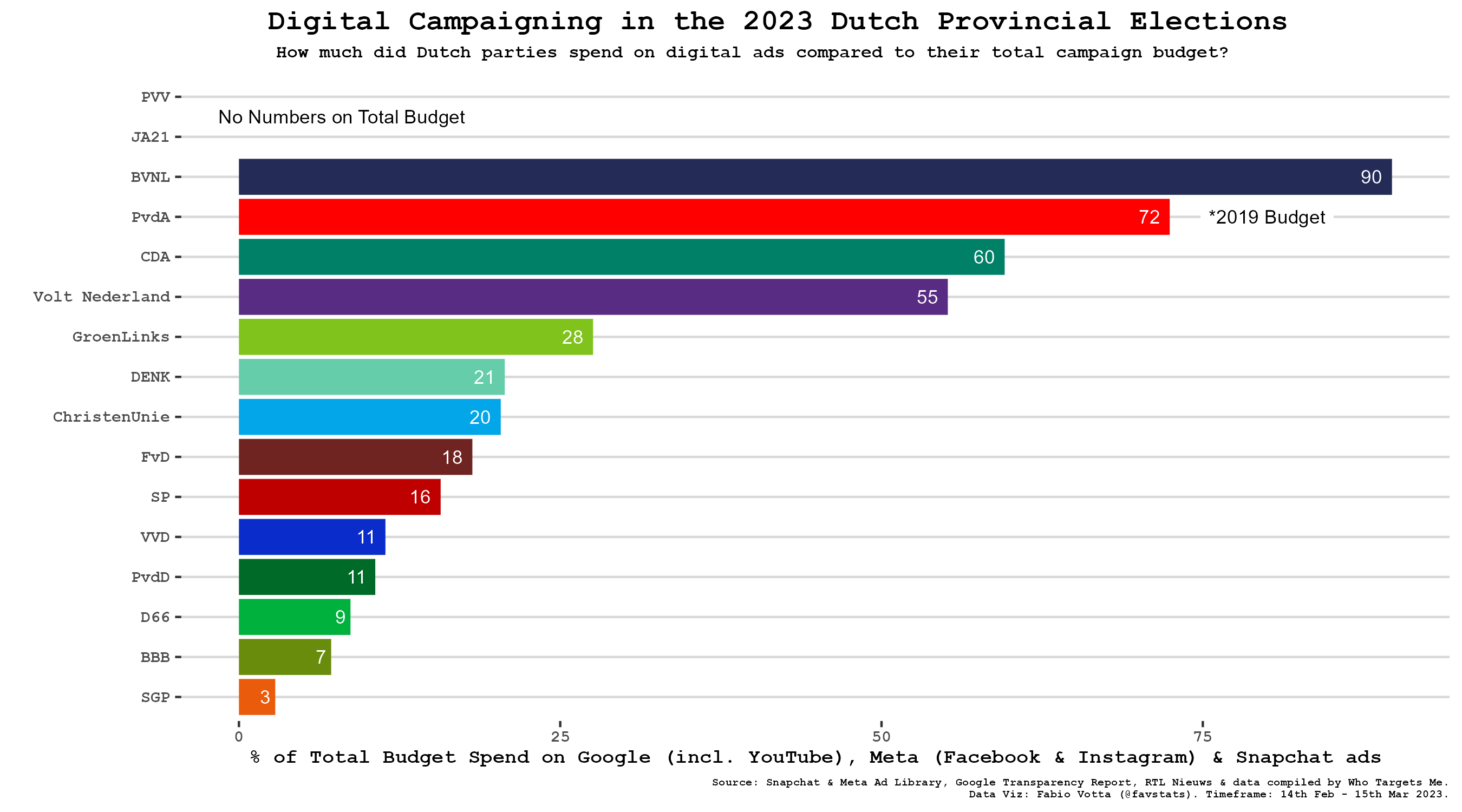

One interesting finding from the data is the percentage of each party’s total budget that was spent on digital ads. In early March, RTL Nieuws published an article in which they researched the total campaign budgets (online & offline) of political parties. Using this information, we calculate that across all parties, the percentage of total budget spent on digital ads ranged from as little as 3% to as much as 90%. The average percentage was around 30%, indicating that digital ads played a significant role in the campaigns.

When looking at the variation in how much money was spent as a percentage of the total budget, some parties stood out. For example, the party BVNL spent a whopping 90% of its total budget on digital ads, while the VVD spent only 11%. Other parties that spent a relatively high percentage of their budget on digital ads include the PvdA (72%) - however this is based on 2019 budget numbers, CDA (60%), and Volt Nederland (55%). On the other end of the spectrum, parties such as the BBB (7%), D66 (9%) and VVD (11%) allocated relevatively little funds to digital ads and focused more on traditional campaign methods such as TV and newspaper ads and posters.

Spending by Digital Platform

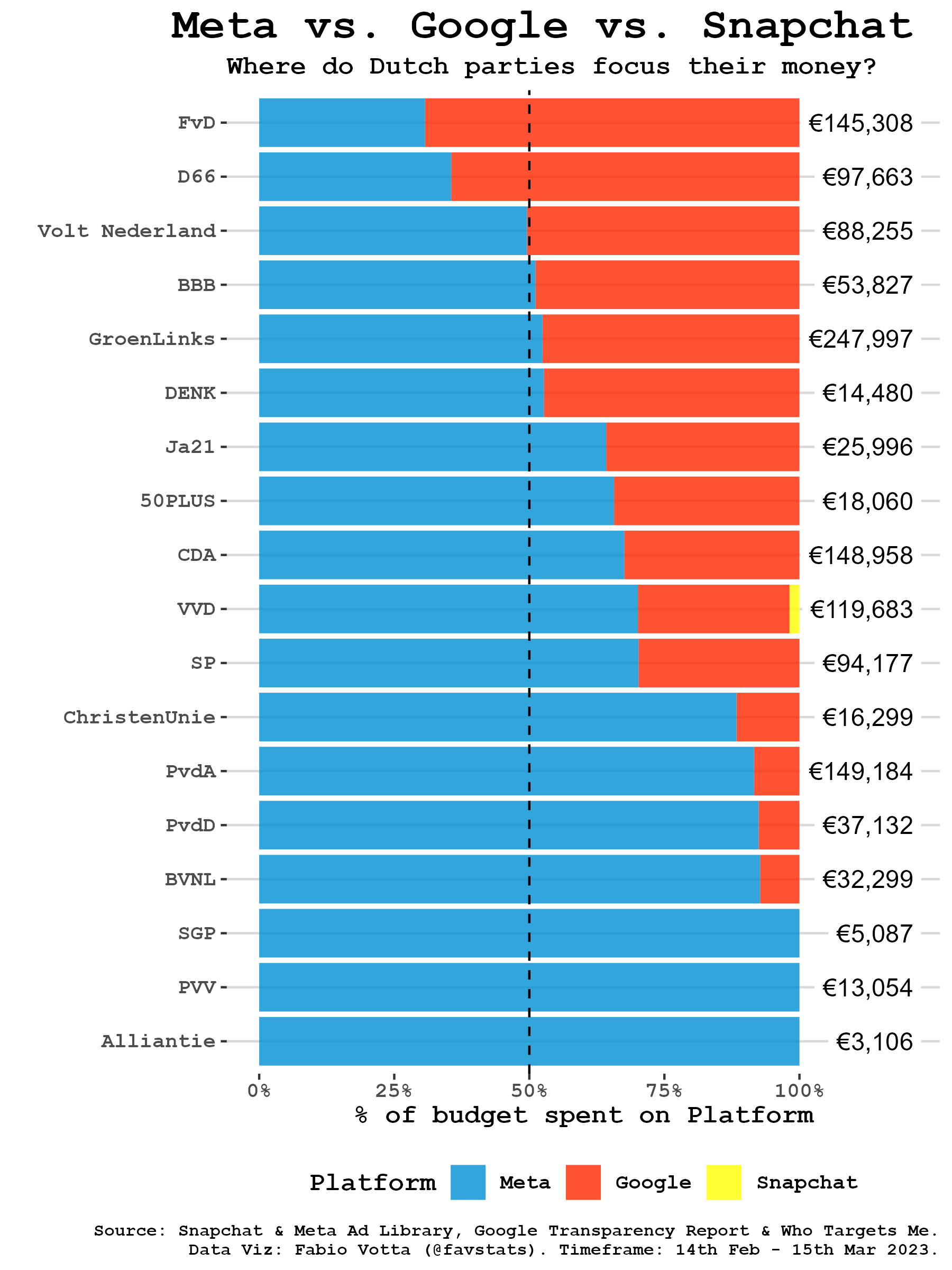

When it comes to the breakdown of spending on different platforms, it’s interesting to note that Meta (Facebook and Instagram) remains a major player, accounting for roughly 61.35% of the total budget spent on digital ads. Google (including Search and YouTube) comes in second place with 38.48% of the total budget, and Snapchat lags behind with only one party, the VVD, spending €2194 on the platform.

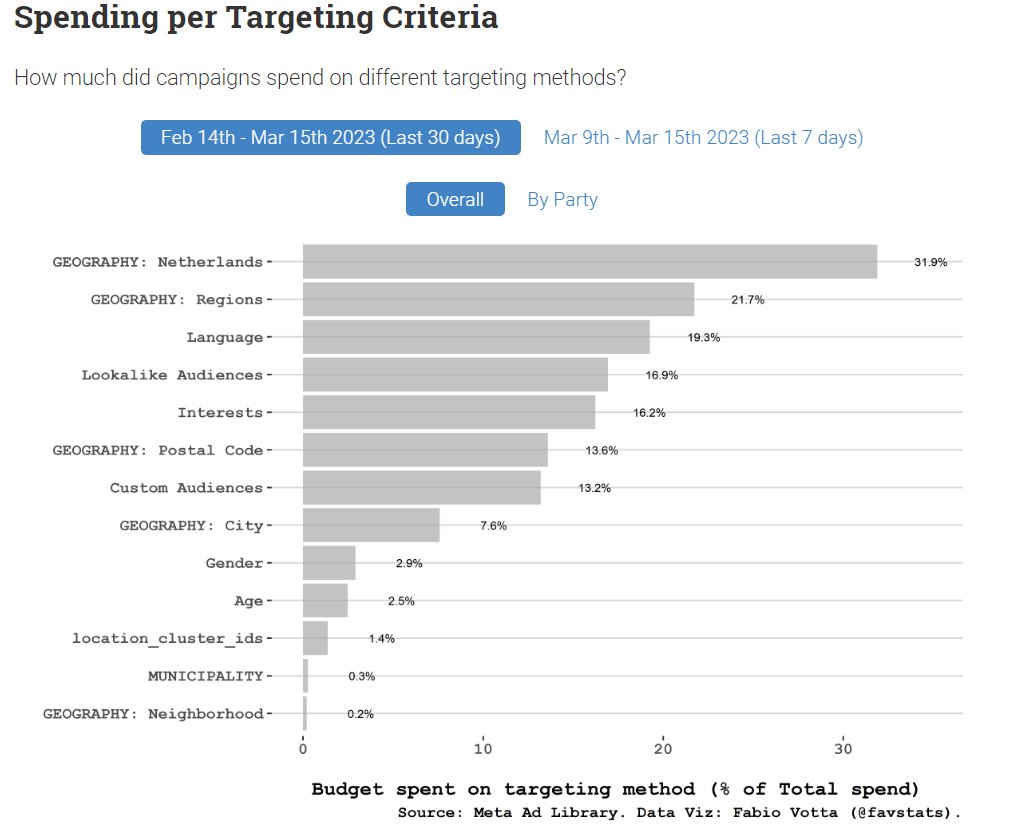

Audience Targeting

This section focuses on targeting on Meta. One popular targeting method here was regional targeting, which accounted for 21.7% of the budget. This is not surprising given that the elections were regional in nature, and parties sought to reach voters within specific regions. This targeting was achieved through location-based targeting, which allows parties to reach voters within a specific geographic region.

Interestingly, age and gender were not heavily targeted by political parties, with the exception of the Partij voor de Dieren, which spent more than half of their budget (52.38%) on targeting women specifically.

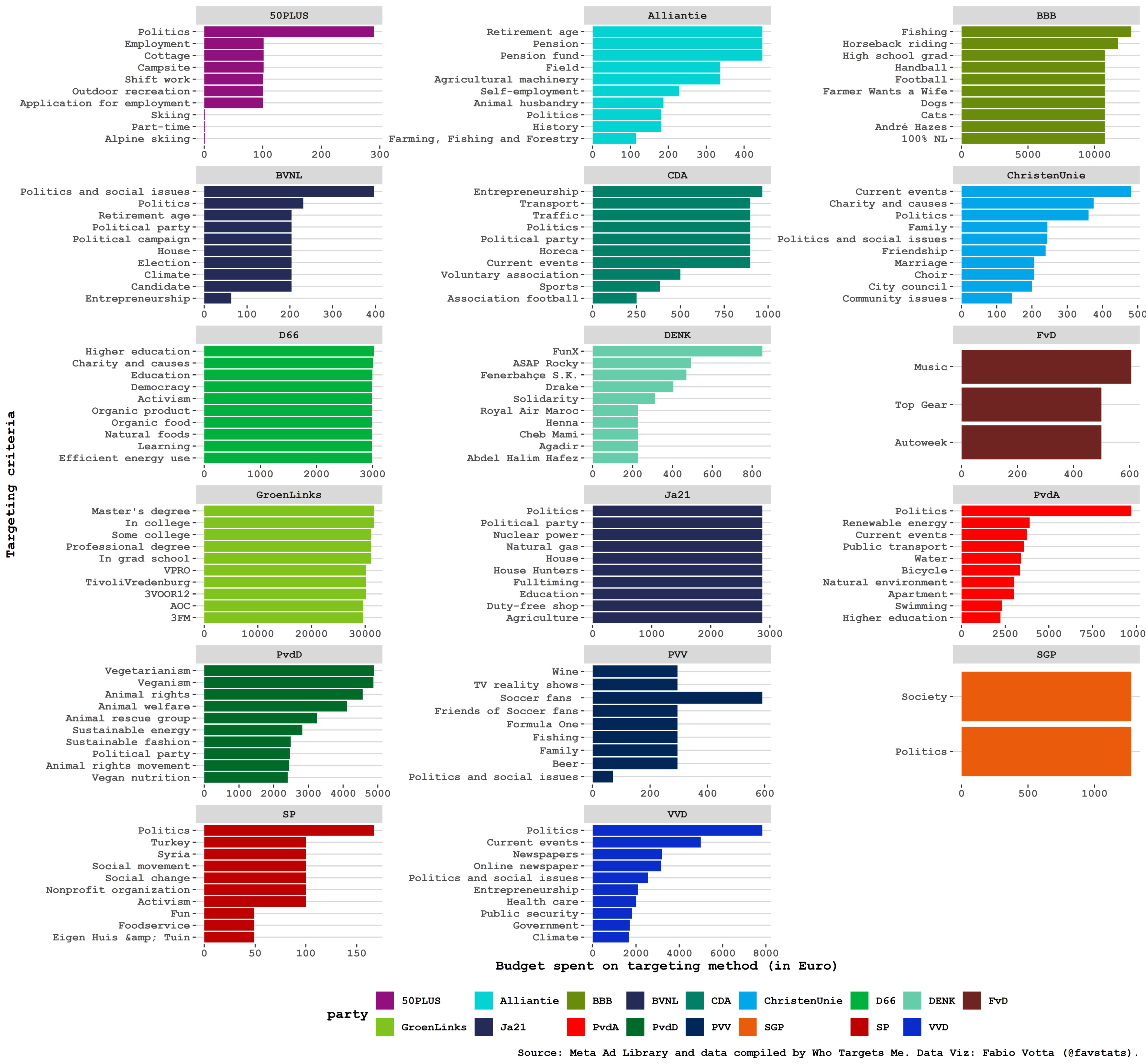

In terms of other detailed audience targeting methods, there were also some interesting patterns. For instance, the GroenLinks party focused on interests related to renewable energy and climate, while the PvdD targeted voters interested in animal rights and veganism. The BBB party, on the other hand, targeted people interested in fishing and horseback riding, fans of André Hazes, and viewers of the popular Dutch TV show “Boer zoekt Vrouw” (Farmer Seeks Wife).

Postcode Targeting

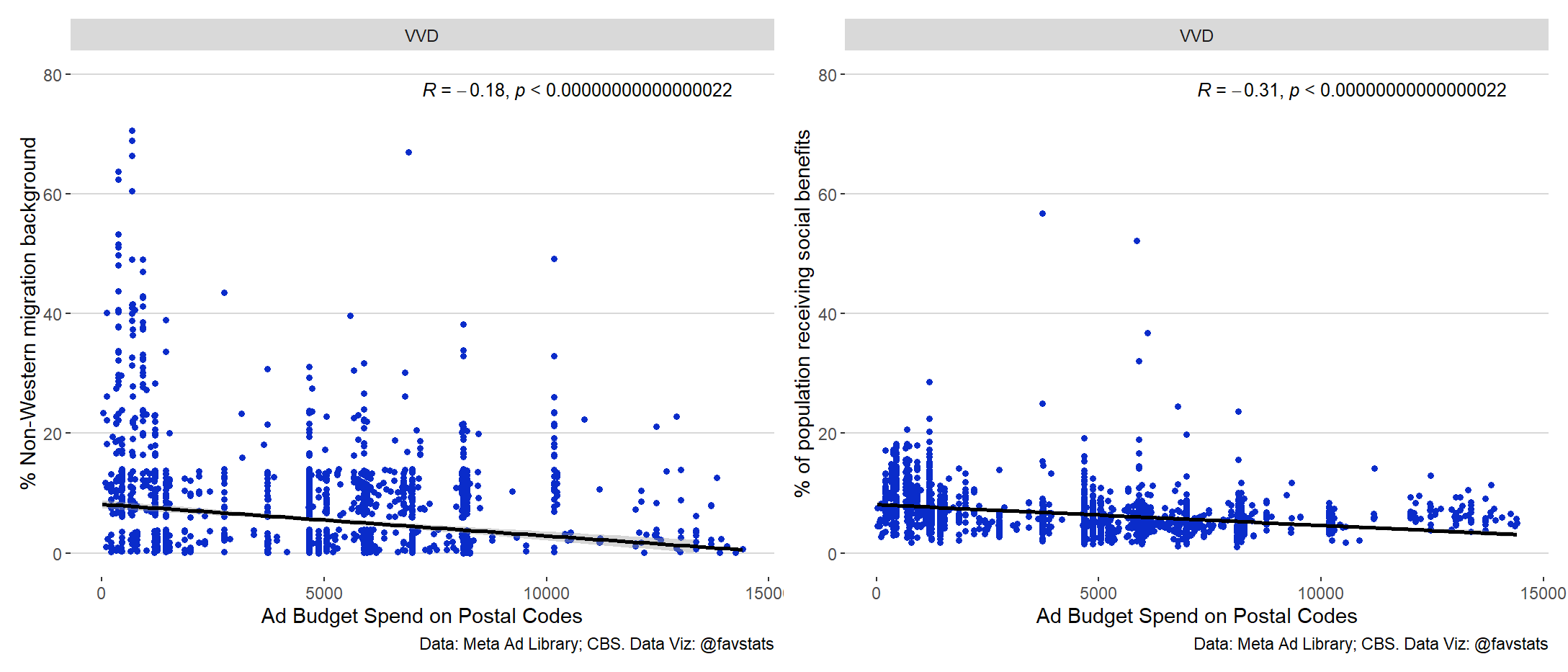

VVD Postal Code Targeting:

The VVD (the party of current Prime Minister Rutte) spent a significant portion of their budget on granular postcode targeting: 27.7% of their budget on Meta. This form of targeting involves identifying specific neighborhoods based on their postcode and sending ads to them specifically.

Matching up the data with demographic statistics, we find a problematic trend: post codes with lower share of people with non-western migrant background (proxy for non-white people) & people receiving social benefits (i.e. more poorer neighboorhoods) were negatively correlated with spending, so the VVD focused on more white, affluent neighborhoods with their targeting.

While granular postcode targeting may seem like a useful tool for political parties, it also raises some ethical concerns. By focusing their efforts on wealthier and predominantly white neighborhoods, the VVD’s digital ads may have excluded marginalized groups which already are likely to be more ignored by politicians.

This kind of targeting can exacerbate existing inequalities in society, as it reinforces and amplifies the preferences and opinions of a particular group. This can lead to further polarization and the entrenchment of political divisions, as people are exposed to information that only reinforces their existing beliefs and biases.

Overall, the use of granular postcode targeting by the VVD highlights the need for greater transparency and oversight in political digital advertising. As the world becomes increasingly digital and political campaigns become more reliant on targeted ads, it is important to ensure that the information being disseminated is fair, accurate, and inclusive.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the digital ad spending during the recent Dutch provincial elections provides us with a unique insight into the complex and multifaceted world of political campaigning. We have seen that parties used a variety of platforms and targeting methods to reach specific voter groups, with Meta (Facebook and Instagram) remaining a dominant force in the digital advertising landscape.

We also saw that parties spent varying percentages of their budgets on digital advertising, with some parties allocating a significant portion of their resources to this area and others focusing more on traditional methods. The targeting methods used by parties were diverse, ranging from regional targeting to interest targeting and more.

Overall, this data provides an important window into the ways in which political parties are adapting to the digital age and seeking to connect with voters in new and innovative ways.

If you want to explore the data for yourself, check out the 🎯 targeting dashboard for more insights on the multifaceted digital ad campaigns used by Dutch political parties during the provincial elections.

Final Words

I would like to give a special thanks to Who Targets Me, a non-profit organization that has made it their mission to increase transparency in political advertising. We heavily relied on their tools and data to gather the information presented in this blog post.

Who Targets Me provides a browser extension that allows users to anonymously share the political ads they see online. They then analyze the data to create reports on political advertising, including targeting methods and spending, across various elections and countries. Their work is invaluable in shedding light on the often opaque world of political advertising.

I encourage everyone to check out Who Targets Me and support their mission of creating a more transparent and accountable democracy.